Today is the first day of Mayor Mike Johnston’s term in office. He is Denver’s first new mayor in 12 years.

Like those before him, Mayor Johnston is greeted with no shortage of urban challenges and a future ripe with opportunity, begging the question: what will he achieve?

Former Mayor Michael Hancock identified the transformation of Brighton Boulevard as the legacy-defining project of his 12 years as mayor.

As he said in in an interview last week:

“I look at the redo of Brighton Boulevard, the rebuilding of Brighton and the attraction of new private development around Brighton and just that whole new area changing. I called it the Corridor of Opportunity…I’m proud of (all) those groundbreaking moments…But I think when you look at Brighton Boulevard and what happened in Union Station under our watch, those are the things that I’m most proud of.”

Brighton evolved from an industrial backdoor to downtown, into a thriving new gateway to the Mile High City. Mayor Hancock put it on par with what Denver International Airport, under Mayor Peña, and Coors Field, Ball Arena (formerly the Pepsi Center) and Empower Field at Mile High (formerly Invesco Field at Mile High), under Mayor Webb, did for Denver.

As part of the core team that helped take Brighton Boulevard from concept to reality, GBSM President and CEO Andy Mountain reflects on Brighton’s transformation and shares seven strategic cornerstones that were key to this legacy-establishing project’s success.

Start with a shared vision.

Beginning from a place of possibility enables bigger and bolder thinking – anything less limits a project’s potential. As an example, our introductory meeting to this project began with an engineer from the City and another from one of the most prominent and influential developers in the area bickering over whether the vehicle lanes on Brighton should be 12 feet wide or 10 feet wide. While space was tight, it made no sense to start with the minutia when we hadn’t even begun fully exploring the opportunity to create something transformative and truly special.

Co-create with the community.

You don’t need a technical degree to be creative and innovative. Often, community members – like frontline employees in a corporate setting – have a clearer sense of the challenges and solutions to a problem than expert planners or corporate executives. We collaborated with the community to bring a diverse coalition of interested individuals together to listen to one another and help us plan and design the future. We engaged longtime business owners, new developers, artists, bike and pedestrian safety advocates, old-guard community members and more. We welcomed them to the same table as our traffic engineers, landscape architects, drainage engineers and other experts on the project team. This established a sense of mutual trust, and it inspired greater motivation among our technical experts to meet the dreams and desires of the local community.

Take calculated risks and admit when you’re wrong.

Brighton Boulevard wasn’t intended to be a legacy-establishing project. While it was one of several projects in the mayor’s “Corridor of Opportunity” , it certainly wasn’t the highest profile of them. And with a limited development area of a one-mile long, 60-80 foot wide stretch of roadway, it was far from the largest project. Throughout the process, we were always clear that we didn’t have all the answers.

For example, one public meeting promised to be quite heated, as the community wanted bike lanes on Brighton and the city engineers wanted them a block off Brighton. Arguably, we could make either work. And both options had their advantages and disadvantages. On the afternoon of the meeting, I sat down with the city’s head of transportation and the executive director of the mayor’s office responsible for the Corridor of Opportunity, and they collectively decided that the community was right: we needed to find the best way to integrate safe bike lanes along Brighton Boulevard.

We opened the meeting by telling attendees that they were right and acknowledged that, while we didn’t quite know how we would be able to adjust the design to incorporate bike lanes, we would challenge the designers to find a creative solution. Seeing a city leader admit they were wrong and double down on a commitment to give the community what they knew was best showed real leadership and was pivotal to establishing trust and true collaboration that benefited the project throughout its development.

Break through bureaucratic norms.

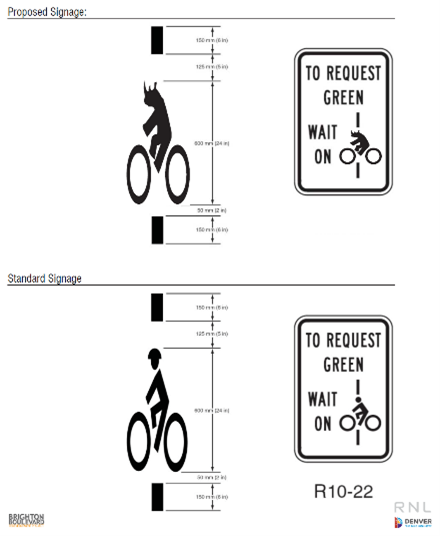

One of the project’s more visible, but simple, moments of creativity started with a landscape architect doodling to entertain himself during a internal coordination meeting on September 3, 2015. He sketched a rhinoceros riding a bicycle. It was a playful homage to the River North (RiNo) Art District that resides in Denver’s Five Points, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea neighborhoods, where the project is located.

I remember snatching his notebook, holding it up to interrupt the meeting and telling the team, “we have to find a way to make this happen, instead of putting typical bike symbols on the bike lanes!”

While some creative street markings were beginning to happen at the time (e.g., piano keys for crosswalks), everyone loved the idea but cautioned my enthusiasm. They knew that we’d have to go through a city process to request variance from the normal street markings. While there were a multitude of bureaucratic concerns (precedent setting, maintenance costs, industry signage standards, and more), it was refreshing to see vision win out and the city’s transportation team approve the RiNoCycle markings that you can now find throughout Art District.

Integrate art early in the process.

One of the biggest mistakes I see cities and private developers make is waiting until after they’ve completed their core project design to begin thinking about public art. This often results in missed opportunities for a cohesive artistic experience, providing well-intentioned, but uninspiring, “bolt-on” additions that feel artificial.

Thanks to Denver’s wonderful Public Art Program, 1% of the project budget was dedicated to public art. Because artists were intentionally included in the visioning process, space for art was reserved throughout the corridor. We finalized art plans early enough to incorporate necessary power that bring to life the interactive LED light sculptures throughout the corridor.

An added benefit of early integration of art was the inclusion of other artistic elements into typical infrastructure design. Functional lighting was creatively inspired. Seating walls and wayfinding signage were collaboratively developed with the RiNo Art District. And while I regret that we weren’t able to integrate RiNo co-founder Tracy Weil’s dream of using luminescent pavement on the bike lanes, embracing artistic and creative ideas like that from the outset of the project helped inspire and elevate the design team’s performance.

Time-limited implementation funding can speed consensus building.

Whether it’s community development or organizational innovation, when there is no implementation funding immediately available, human nature often takes over and people go overboard debating what could or should be done, instead of focusing on getting things done.

As president Obama recently advised in an interview with LinkedIn’s editor-in-chief, “just learn how to get stuff done.”

The way I think about it, talk is talk. But action is impact.

We had three favorable funding elements on Brighton Boulevard. First, we had the private-funding benefit of a number of developers actively in their design and/or permitting phases. They were motivated to help the city figure out its design so that theirs would effectively integrate. Second, Mayor Hancock identified some expiring one-time funding that he dedicated to implementing the project. Finally, we were helping the RiNo Art District form two special districts: a broad Business Improvement District to fund district-wide placemaking efforts and a General Improvement District to fund Brighton-specific infrastructure elements. We were able to use the motivating power of these financial forces to focus timely consensus building and decision making to keep the design process on schedule so that we could transition directly into construction.

Accept that change won’t always be pretty or perfect.

Change is never easy. And you don’t always win. For example, many in the community assumed that Denver’s Urban Renewal Authority would declare the area “blighted.” This would have created the opportunity for Tax-Increment Financing to help take the project to the next level by integrating and accelerating, additional public investments in the community, such as parks, riverfront enhancements, improved pedestrian connections and more.

While this didn’t happen, the overarching vision we were able to establish for the area provided the public and private sectors with the perfect roadmap and well-supported vision for the ultimate developments that have emerged in the years since the Brighton Boulevard project was completed.

Mayor Johnston is inheriting a number of challenges and opportunities as he starts his term. Many of the lessons Mayor Hancock’s teams learned through the design and development of Brighton Boulevard can provide valuable guidance and motivation to help Mayor Johnston and his administration as they work in partnership with the community to shape the future of Denver and build their own legacy.

Photo credits: Stantec, Andy Mountain, The RiNo Art District and the City and County of Denver.